I Built a Coding Agent in 90 Days. Here’s How It Actually Works.

From a basic API wrapper to a production-ready agentic environment

Almost all useful agents today are coding agents. Instead of interacting with an application through the UI, agents are now writing code to make slides, excel sheets, or browse the internet. In the past 90 days, I built my first coding agent from scratch (Chippy.build, an ai prototyping tool for ChatGPT apps).

This post breaks down how it works, what makes coding agents different from other AI applications, and what I learned along the way. Let’s dive in!

What Makes an Agent Different

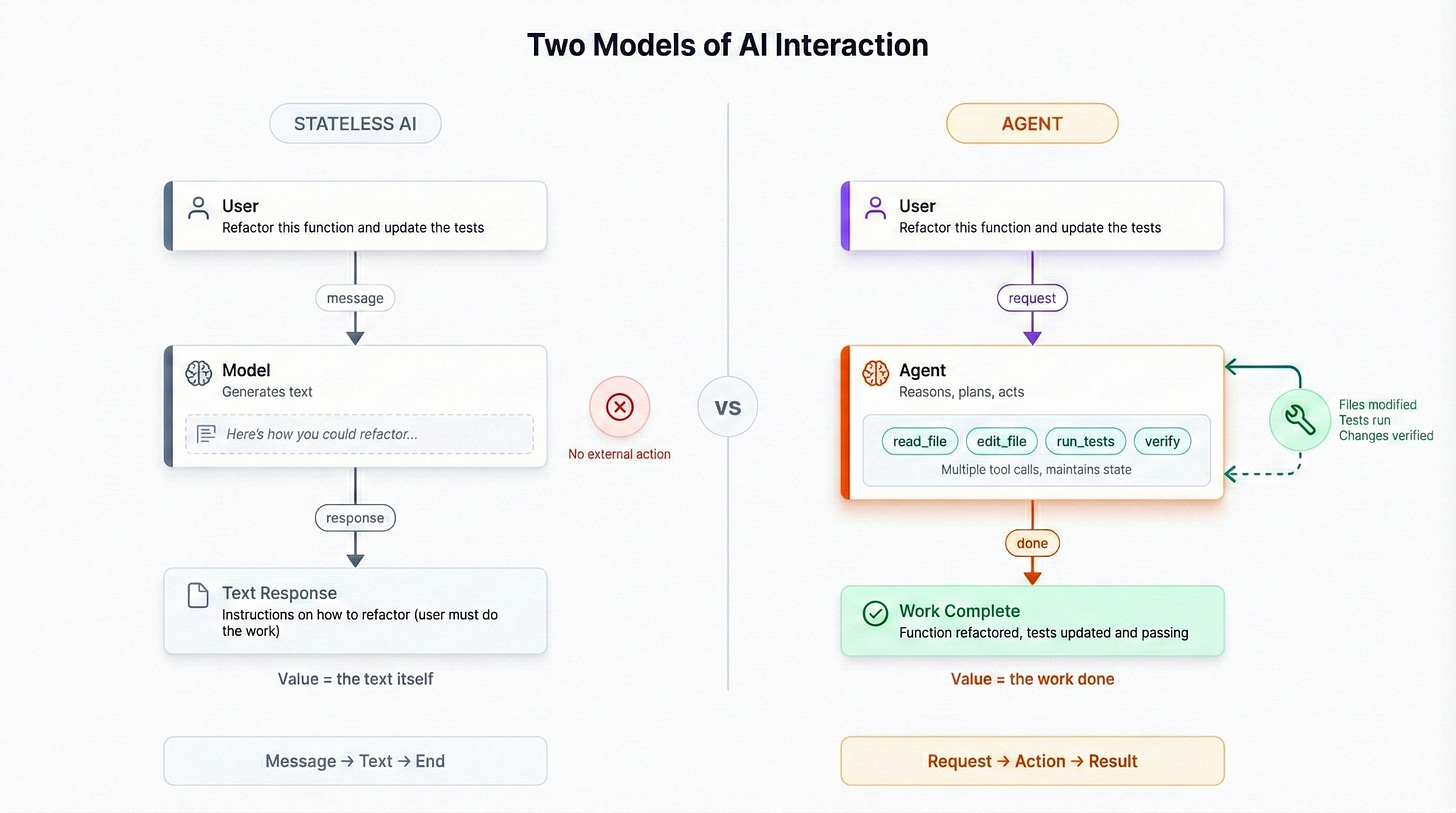

The most common use case for AI applications today is generating text. Whether it’s finding a recipe or helping you write a paper, most people use tools like ChatGPT and Claude as text-based assistants. You send a message, you get a response, and that’s the end of the interaction.

An agent is different. An agent can use tools, maintain state across multiple turns, and work toward a goal that might take many steps to achieve. When you ask an agent to “help me book a vacation” it actually does it, searching flights, reserving hotels, and blocking your calendar. In this model, the valuable part is not the text response, but instead the work done between the user’s request and the agent’s response.

The distinction is important because it changes what you’re building. A chatbot needs good system prompts to present a coherent persona and may need access to external data sources like websites or files. An agent needs good system prompts and a runtime that can execute tools, manage state, handle errors, and verify results. The system prompts are maybe 30% of the work. The other 70% is the harness.

On top of this, coding agents are a degree more complex than regular agents. Where a regular agent may have one way to solve a problem, coding agents have near infinite. Here’s why:

Code has to actually run. If you ask an agent to write an email, it can produce something plausible and you’ll judge whether it’s good. If you ask an agent to write code, there’s an objective test: does it execute without errors? This creates a tight feedback loop that other domains don’t have.

Code exists in files and files have relationships. Changing one file might break another. The agent needs to understand not just the code it’s writing but the context it’s writing into.

Users expect to see results immediately. When you change a UI component, you want to see the updated preview right away. This means the agent needs an execution environment and a real-time preview; you can’t just return text and call it done.

Evaluating the quality of coding agents is more challenging. Most coding problems can be correctly solved with many different approaches, so you can’t anticipate all possible correct answers to verify if the agent is behaving properly. Instead, you have to read traces to find common errors and build evaluation sets based solely on the final outcome of the agent.

These constraints shape the overall design and architecture of a coding agent. We’ll take a look at how this works using Chippy as an example.

The Core Loop

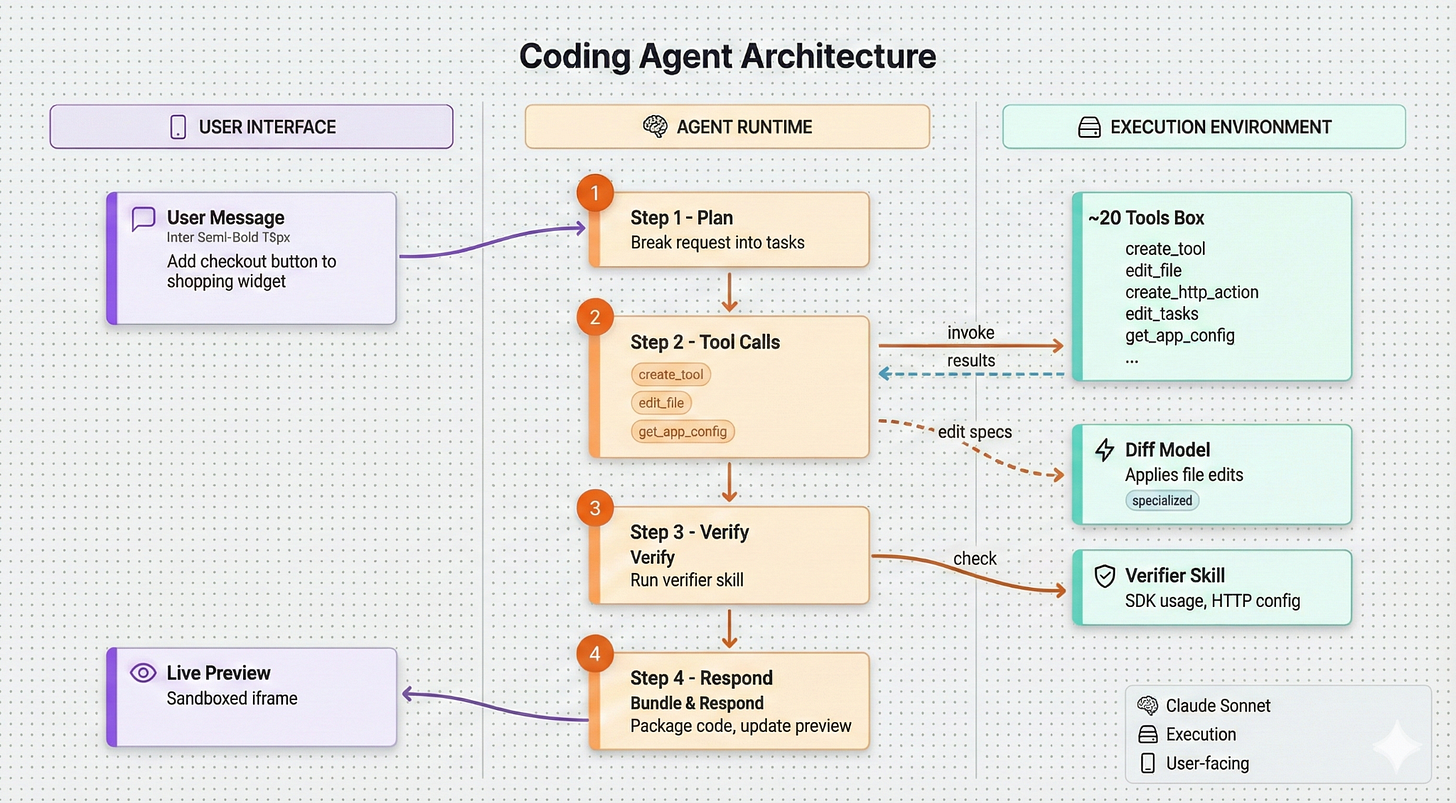

Every coding agent follows the same basic pattern.

The user sends a message describing what they want.

The agent plans the work by breaking it into steps.

The agent calls tools to read files, modify code, and interact with the environment.

It verifies that the changes work.

Then it responds and updates the preview.

Oftentimes there are some visual updates as the agent is working, such as showing tools called or lines of code written. Good UX for demonstrating progress during these long running processes is critical.

Here’s how this was implemented inside of Chippy:

That’s the loop: message, plan, tools, verify, respond. If you understand this pattern, you understand 80% of how coding agents work. It’s surprisingly easy to get a basic coding agent working, but a high quality agent is built in the details.

Chippy’s agent runs on the Anthropic API with a custom runtime. I didn’t use LangChain, the OpenAI Agent SDK, or Anthropic’s Claude Code SDK. I tried these frameworks but I found that they had some core assumptions about the environment they’d be running in that didn’t 100% align to my vision. Additionally, I found using these frameworks abstracted away the core agent loop and made it more difficult to learn how these systems really work.

Building a custom runtime sounds more intimidating than it is. Any LLM provider gives you everything you need: you send messages, the model returns tool calls, you execute them and send back results. The “runtime” is really just a loop. The complexity isn’t in the infrastructure - it’s in the tools themselves and in making the whole system reliable.

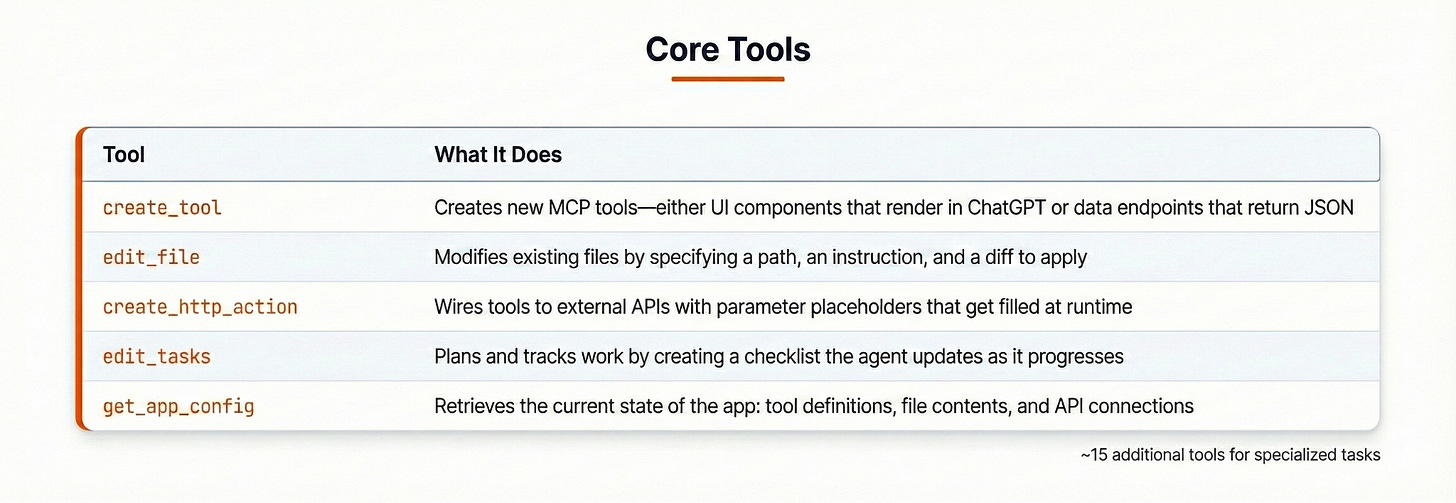

Chippy’s agent has about 20 tools. Here are the five that do most of the work:

Let me trace through what happens when you tell the agent “Add a checkout button to the shopping widget.”

First, the agent calls edit_tasks to plan the work:

{

“tasks”: [

{ “label”: “Find the shopping widget component”, “completed”: false },

{ “label”: “Add checkout button with onClick handler”, “completed”: false },

{ “label”: “Wire button to checkout flow”, “completed”: false }

]

}

This does two things: it makes the agent’s thinking visible to the user, and it gives the agent a structure to follow. Without explicit planning, agents tend to jump straight into code changes and miss steps.

Next, it calls get_app_config to understand what exists. The response includes current tool definitions, file contents, mock data, and API connections. The agent now knows the context it’s working in.

Then it calls edit_file to modify the component:

{

“path”: “ShoppingWidget.tsx”,

“instruction”: “Add checkout button below the cart items”,

“edit”: “- </div>\n+ <button onClick={handleCheckout}>Checkout</button>\n+ </div>”

}

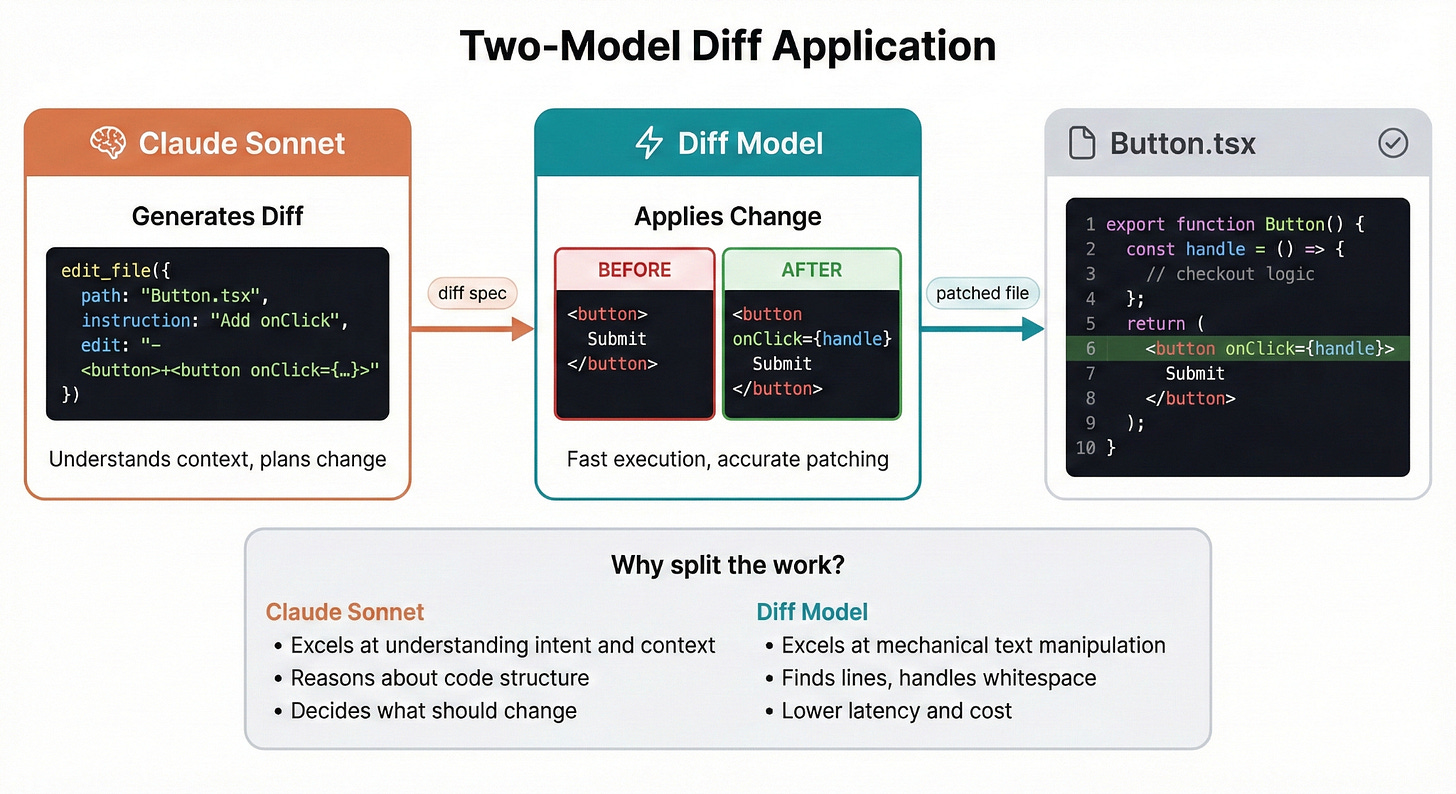

In Chippy, Sonnet doesn’t apply the diff directly. Instead, I use a Small Language Model (SLM) to apply diffs. Originally I had Claude using a tool for string replacements, but it would often get white spaces or other small issues wrong that would cause the edit to fail.

The next iteration of edits was to use the File tools offered by Anthropic. I found that these tools conflicted with other beta features such as programmatic tool calling and were difficult for me to iterate on to improve performance.

The final interaction was to have Sonnet generate a text response of what should change and use another model fine tuned to make accurate code changes to apply the change. This handled a lot of edge cases and small issues without using the more expensive Sonnet model and multiple retries.

The practical benefits are significant: lower latency per edit, lower cost since smaller models are cheaper, and fewer mistakes on the actual text manipulation. Claude focuses on the hard part, and the diff model handles the easy part.

Once the edit is finalized, we run through the verification steps. For my agent, that means:

Bundle the code

Run the verifier skill

Bundling the code is pretty simple. This takes the original code written by the agent and attempts to transform it to what will be displayed on a web browser. If this process fails, the agent gets an error message and modifies the code to reattempt.

The verifier skill is more interesting. In case you’re not familiar, a skill is like a prompt that the agent can choose to load when the user needs it. It allows your agent to ‘download’ new instructions at the right moment in time. A good analogy is like Neo downloading new skills in the Matrix.

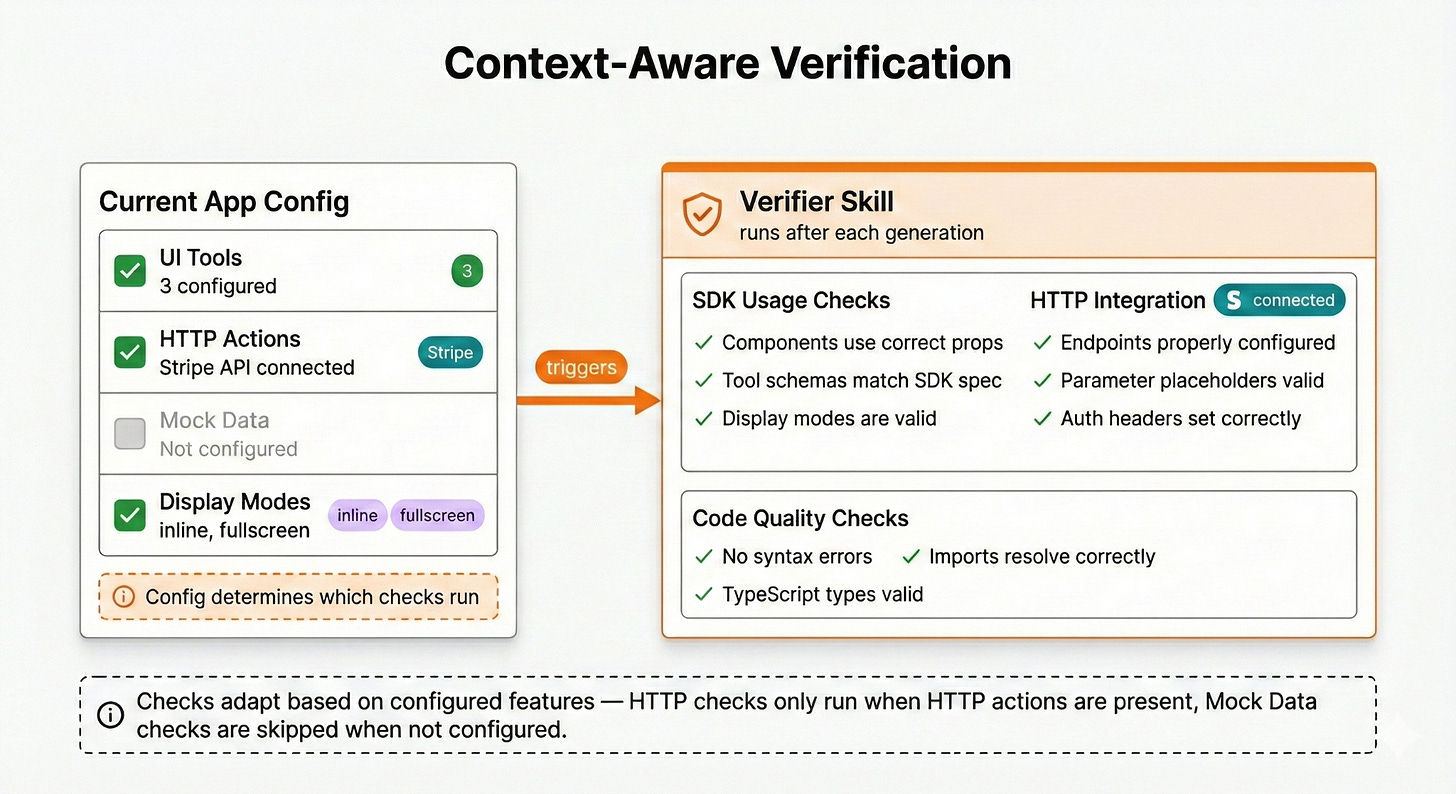

My verifier skill is a structured set of checks that runs at the end of each code generation, like a code review that happens automatically before the user sees the result. It’s also context aware, meaning that the instructions loaded will match the set of features currently being used. This helps to avoid situations where the agent incorrectly applies checks for a feature that’s not currently in use.

This approach has caught a lot of errors that would have otherwise shipped to users.

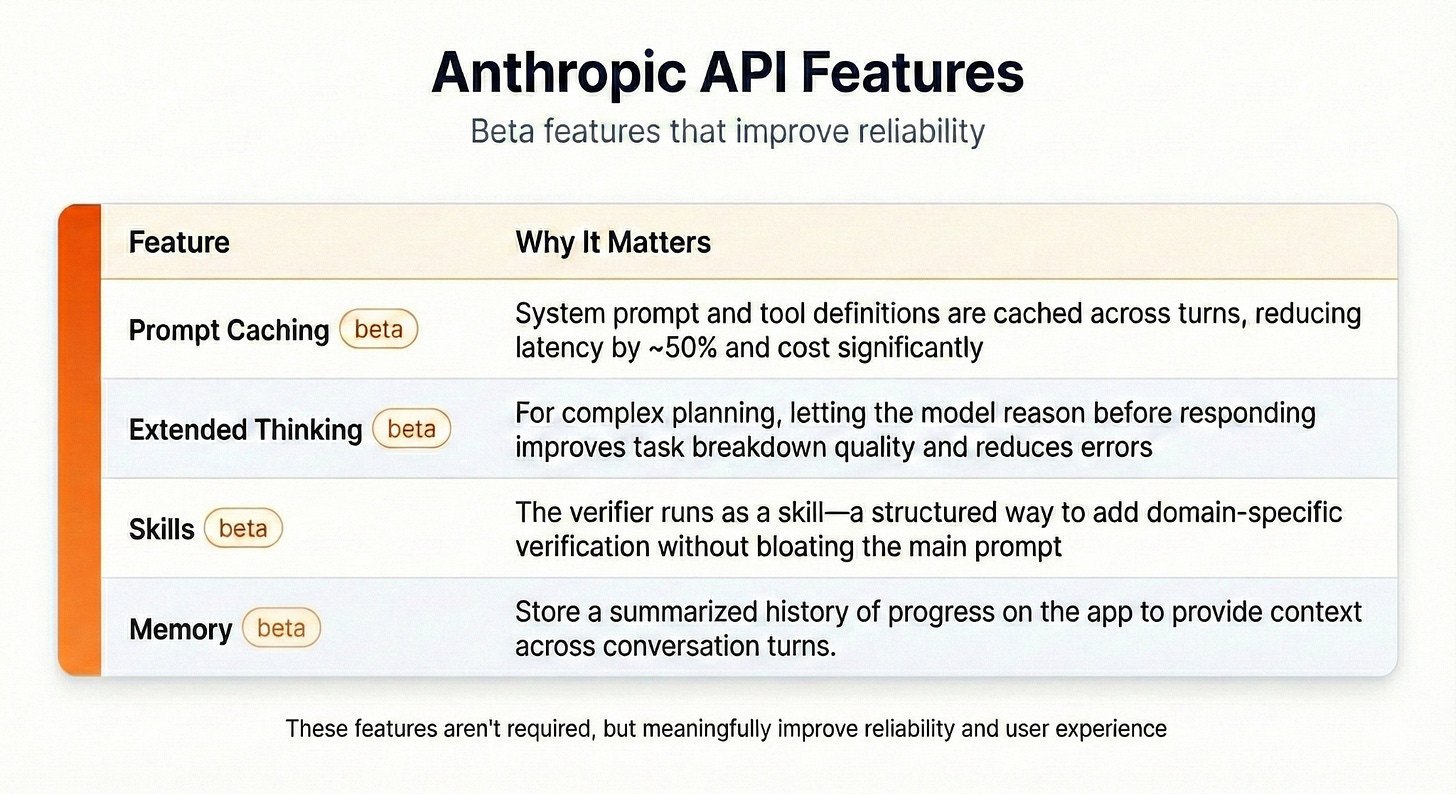

I also use several Anthropic API features that make a meaningful difference, such as prompt caching, interleaved thinking, and memory management.

These features aren’t strictly necessary, but they meaningfully improve reliability and user experience and the integration cost is low.

What I Learned

Here’s my top takeaways after spending the last three months building a coding agent:

1) The Core Loop Is Simple

Building the basic agent loop took about a week. You need three things: a tool for modifying files, an environment to run those files, and a preview to show the user. If you have experience building with the Anthropic or OpenAI APIs, the jump to building an agent is smaller than you might expect.

2) Reliability Is the Real Work

The gap between “works” and “works reliably” is where I spent most of my time. I read through hundreds of execution traces looking for failure patterns. Some problems yielded to better prompts. For example, if the agent kept forgetting to plan first, I could emphasize planning in the system prompt. Other problems required structural solutions like the verifier skill. Giving the agent a way to test its changes and clear error messages was critical to improving reliability.

The honest assessment is that prompt engineering gets you maybe 30% of the way to reliability. The remaining 70% requires building systems around the model: verification, error handling, and careful tool design.

3) Frameworks Encode Assumptions

Every agent framework I evaluated came with assumptions about the environment: local filesystem access, specific conversation structures, particular ways of handling tool results. These assumptions make frameworks easier to use for their intended use case. When your use case differs, you spend more time working around the framework than building your product.

For Chippy, the right choice was building a custom runtime. The Anthropic API is flexible enough that the infrastructure is simple.

In case you’re curious, I worked for about 10 hours a day, six days a week to build Chippy. Here’s roughly how the time broke down:

Weeks 1–2: Core loop implementation, basic tools, first working prototype that could actually modify files and show a preview.

Weeks 3–6: Tool refinement and prompt engineering. This is where I discovered most of the edge cases and failure modes.

Weeks 7–10: Verifier skill development, diff model integration, systematic reliability improvements.

Weeks 11–13: Polish, testing, and launch preparation.

The first prototype came together quickly. Making it production-ready took the remaining 11 weeks.

One more thing worth mentioning: I used Claude Code to write about 90% of the code!